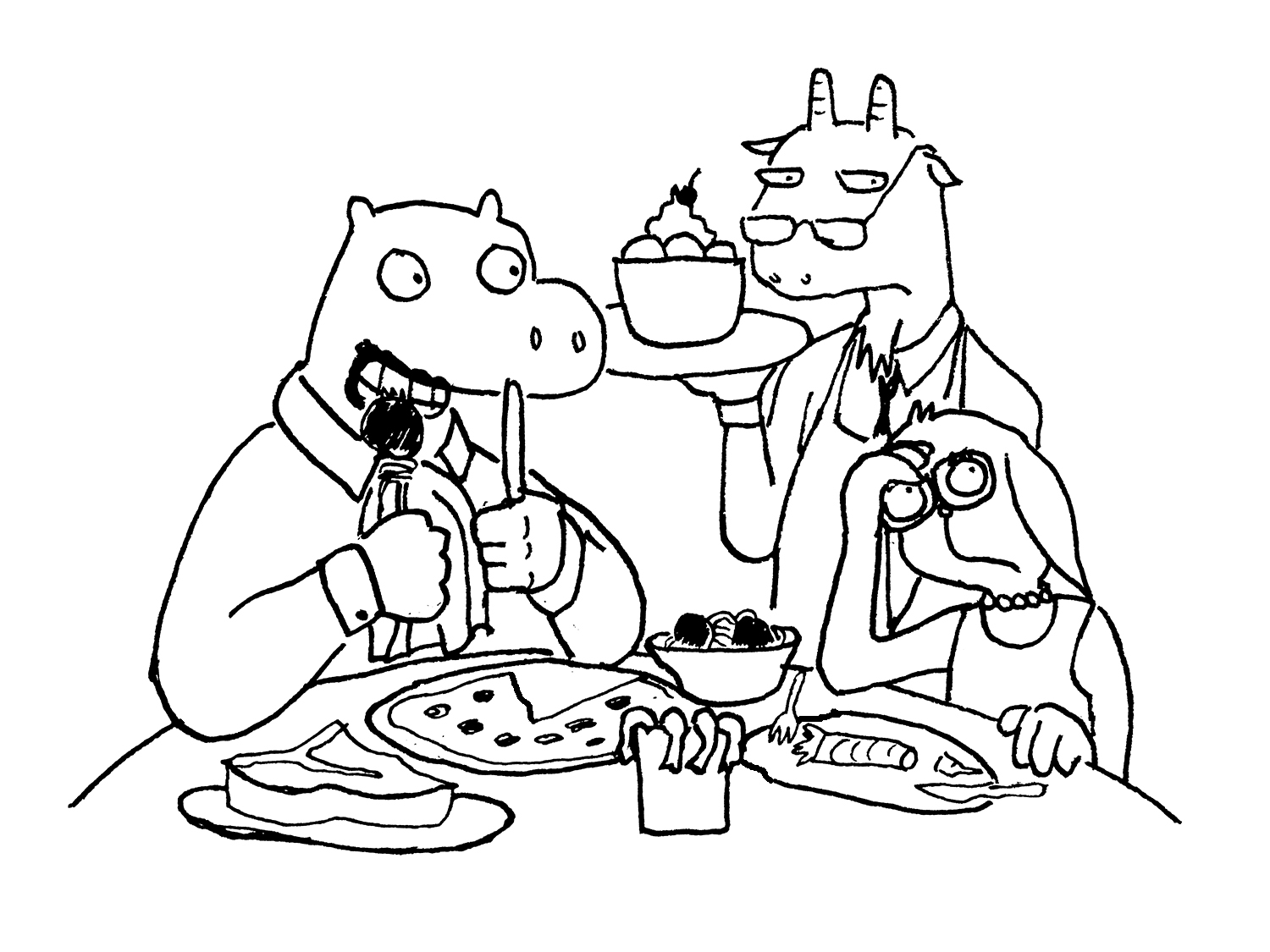

ILLUSTRATION: Hippo Embarrasses Bunny at Dinner… Again • ink • 3×5″

I recently finished my sixth or seventh viewing of the 2002-2008 HBO series The Wire—that might seem like a lot (~400 hours), but they say TV reruns reduce stress. After a number of crappy startups and countless breakups, it’s The Wire—of all potential sources of comfort—that is my fix.

The Wire explores class, race, money, business, bureaucracy, among other themes—in other words, modern America. I think the show stands along with the documentary Hoop Dreams as the most accessible and valuable criticism of our society in the last twenty years. It’s one of the best pieces of fiction I’ve ever consumed across all formats. If you haven’t seen it yet, just stop reading this and come back in a few weeks. Maybe take some sick days.

Ready now? Great.

The Wire uses recurring dialogue, motifs, and parallelism to hammer home its themes, and one construct that stood out on this watching is the consistent use of meals to critique class mobility. In the first season, D’Angelo Barksdale and his girlfriend Donette visit a stuffy, upscale restaurant in Baltimore—waiters in suits, dessert carts, middlebrow, couples in their balding and short perm years respectively, tonally if not actually white.

Underdressed and arriving without a reservation, D’Angelo is markedly uncomfortable, asking Donette whether the folks around him suspect that he’s involved in drugs, that he’s a gangster. Donette argues, “Your money’s good right? We ain’t the only black people in here.” But D’Angelo is unable to fully explain his discomfort, just that there are things that stay with you, that “as hard as you try, you still can’t go nowhere.”

Donette has none of it. “Boy, don’t nobody give a damn about you and your story. You got money, you get to be whoever you say you are. That’s the way it is.” Her argument takes an immediate hit when D’Angelo picks up a sample dessert from the cart—the way you would at a cafeteria—before being admonished by an effeminate waiter. The action says more about class than any of the perhaps-too-on-the-nose dialogue that precedes it. D’Angelo is painfully aware of the gap between him and the “other” world around him while Donette is unaware of her own similar distance to the other world.

“For another pit sandwich and some tater salad, I’ll go a few more.” –Wee Bey

D’Angelo and Donette’s dinner scene is not the only mealtime exploration of the intransigence of class in the show. In Season Three, a leather-jacketed Detective Jimmy McNulty tries to bridge his blue collar world with the white collar one of a political operative on a date at an upscale southern restaurant in DC, only to find something similar to D’Angelo, that the woman looks through him, that his world doesn’t exist. In Season Two, parallel meals between Detective Kima Greggs, Lieutenant Cedric Daniels, and their respective partners in complete silence highlight a struggle over ambition and social climbing. Their partners want them to choose law over order, money over love, white collar over blue collar.

For Stringer Bell, his suit-and-glasses-lunch with Clay Davis and real estate developers in Season Three gives us yet another depiction of the truism, “if you look around the table and can’t figure out who the sucker is, it’s you.” Or more directly from Avon Barksdale when he encapsulates the concept of social distance for Stringer: “I look at you these days, String, you know what I see? I see a man without a country. Not hard enough for this right here and maybe, just maybe, not smart enough for them out there.” (More on Barksdale versus Bell another time)

But the most obvious redux of D’Angelo’s scene comes in Season Four when former police major Bunny Colvin takes “corner kids” to a Ruth’s Chris at the harbor as a socialization experiment where we get another depiction of how foreign the customs and mechanics of a restaurant can be to someone who’s never been somewhere other than McDonald’s. Being waited on. Handing over your coat. Choosing a temperature for your steak. When to use a straw. What a special is. The fact that no one else in that restaurant would spend three hours on their hair, but of course Zenobia would—this is special to her in a way that it might not be to regular patrons.

Unlike some of the other meals, however, I’d argue that this dinner says something positive about overcoming social distance, that perhaps it’s not intractable over generations. Bunny’s taking Namond on as a ward and his flourishing gives weight to that argument.

That’s something positive for a change, right?

In the context of the show, if not life, both D’Angelo and Donette are probably right about money and class in their own way.

As with any good tragic flaw, it’s D’Angelo’s self-awareness that prevents him from overcoming the gap in class he so clearly sees. For D’Angelo, he will always be betwixt and between two different worlds. His story ends in the second season after fittingly discussing The Great Gatsby in a prison book club when he explicates what he tried so hard to do at that dinner with Donette.

He tells his fellow inmates, “It’s like, you can change up. You can say you somebody new. You can give yourself a whole new story. But what came first is who you really are, and what happened before is what really happened. And it don’t matter that some fool say he different, ’cause the only thing that make you different is what you really do, or what you really go through.”

As for Donette, she can be who she wants because it’s unlikely she’ll ever see the gap; there’s no harbor to cross to reach that green light. It’s right there to be grasped.

P.S. There’s a webcomic coming soon from Bryan Keefer and me, but it means that I may be even more sporadic in my posts over the next couple of weeks. More soon.