Read Part I: Sneakers, Fire Fighters, and McKinsey or Part II: Fun with DCFs and Stock Comp.

If you were a technology CEO, wouldn’t it be great if you could issue all the stock you wanted to employees without your investors minding a bit? That’d be pretty awesome. And what if those investors also rewarded you for controlling your cash operating expenses, especially in this time of bubblicious salary increases for engineers? I think you’d be pretty excited about that, as a tech CEO, or even one of the employees.

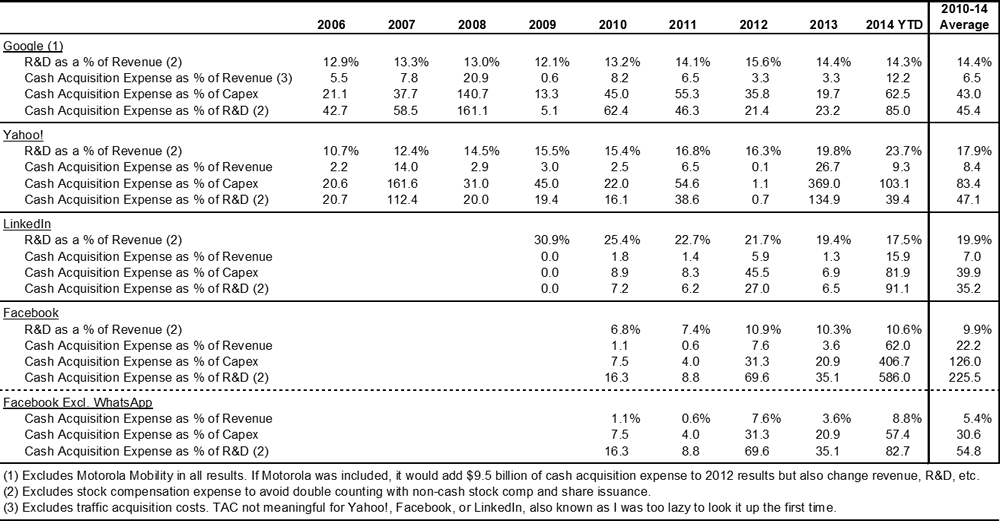

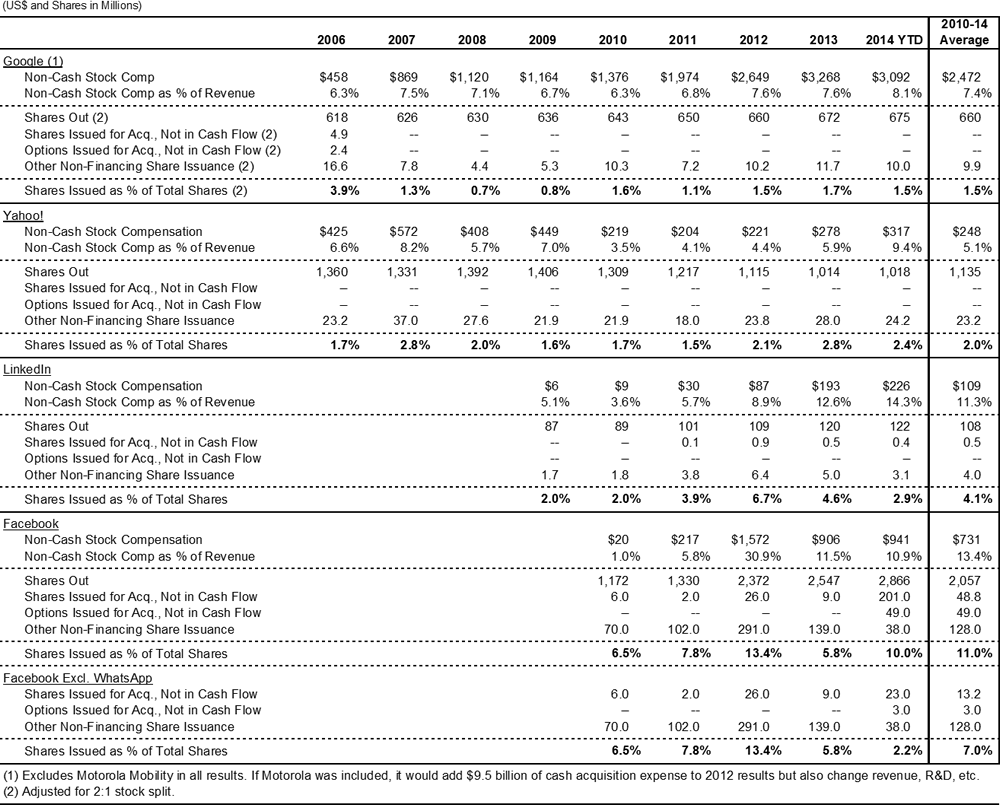

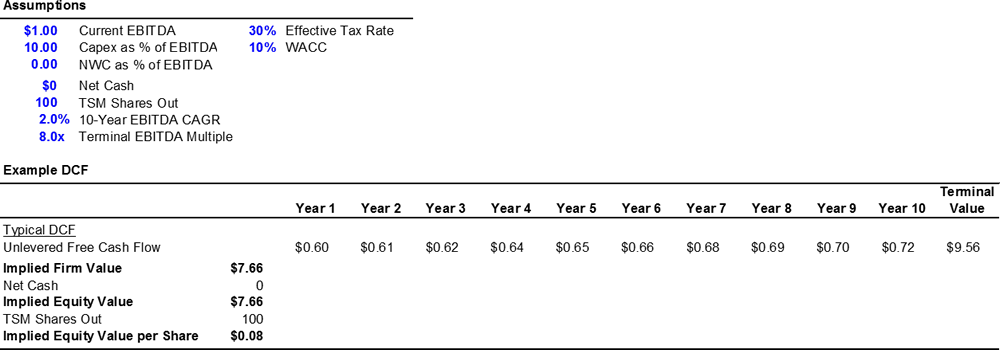

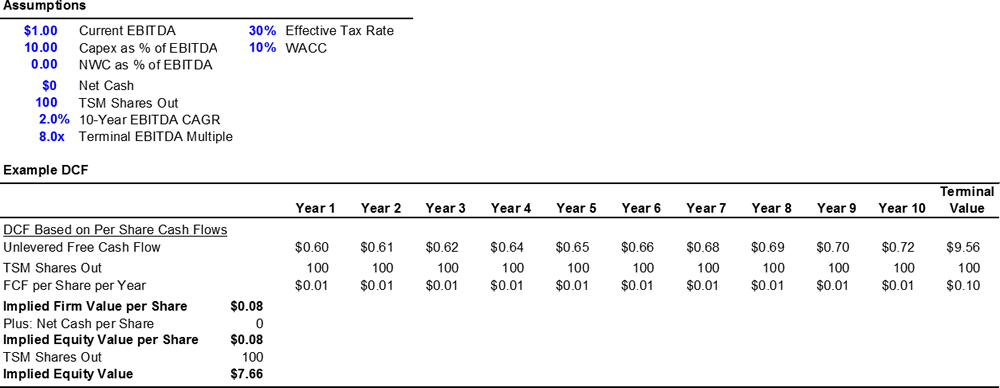

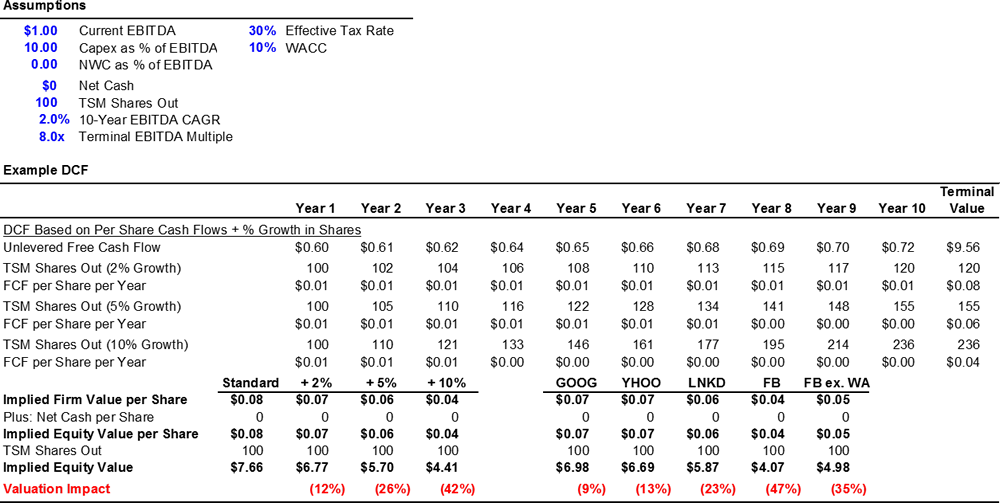

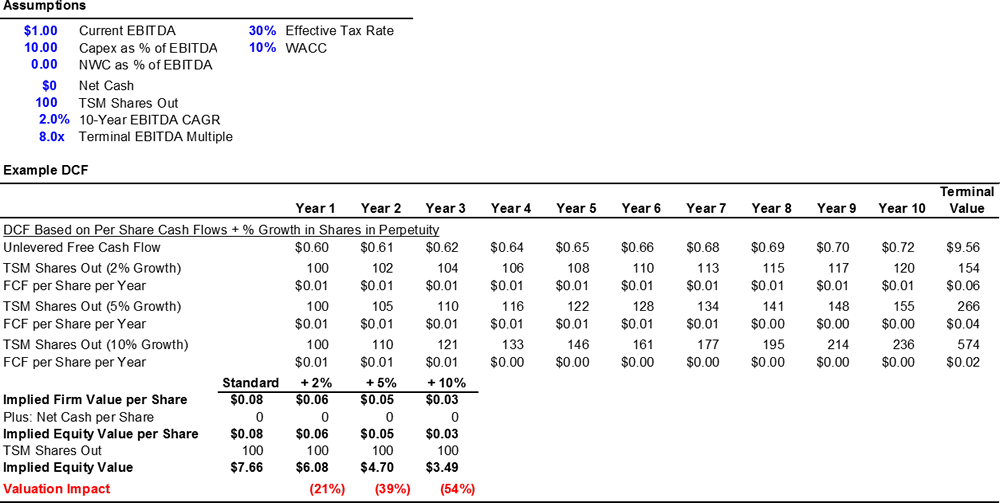

Previously I argued that today’s Internet companies such as Facebook and LinkedIn might be issuing more shares for compensation and acquisition to stay competitive in this environment. I then argued that adjusting valuation methodologies to account for continual equity dilution would result in major (25-50%) reduction in market valuation. Neither traditional DCFs nor cash EPS multiples capture the future impact of stock issuance or the cost of buybacks to keep dilution to a minimum, and I know from work as a research analyst that share counts are given short shrift.

But why do we ignore it? Is it because buybacks only happen on the cash flow statement (and below the traditional “line” too)? When it comes to acquisitions, is it because we no longer amortize goodwill making acquisitions look like either a revenue boom or an impairment bust? Or is it because some other accounting rule blinds us to the ongoing impact? It could be any, all, or something else.

I posited that many casual investors (and not-so-casual ones) might not appreciate the shift to restricted stock units (RSUs) that has become commonplace as a replacement for stock options in Silicon Valley technology companies. Being ignorant of the ongoing accounting for restricted stock compensation myself, I decided to dig more deeply for my own benefit and those of my seven readers.

Based on my research, I think that the permanent impact of restricted stock dilution isn’t reflected well enough in traditional financial reports, and we need to pay better attention to the growing levels of non-cash stock compensation when valuing companies absolutely or on a comparable basis.

Disclosure: Of the stocks mentioned, I’m still net-long Google, and net-short Facebook. I recently ended a net-short position in Twitter. The numbers are very, very, very small, because I have partaken neither in the Bay Area tech bubble nor Bay Area real estate one to a material extent. I’m also not a CPA, and my most important primary source has been this PwC report on accounting for stock-based compensation.

Disclosure #2: I’ve been working on this post for a long time between other projects, and I just want to get it out—hence no illustration. If there had been an illustration, it would have been titled “Clay Davis / ‘Whatever that was, they don’t teach it in law school.’” Maybe I’ll add it in the future.

Let’s start off with a short review of how stock options and RSUs work. I’m going to limit my analysis to public companies.[1]

For public companies, stock options are granted to an employee and represent an option (duh) to buy a share at an exercise price which is the current trading price of the stock. If your stock is priced at $10.00 per share when you are granted an option buy it, then your option has exercise price of $10.00 per share. At the time, your option has no intrinsic value to you. You could just as well buy a share on the open market for $10.00.

But options also have “time value” because you’re able to buy that share for $10.00 up to ten years later as long as you’re still employed by the company. This “optionality” has value, and math people smarter at stuff like this have developed equations using volatility and standard market returns to calculate time value that when combined with intrinsic value results in a FAIR VALUE for the option. This is what the option is worth on its own, as an option, before you exercise it. Maybe that fair value is $5.00, and we’re going to use that for simplicity sake.

RSUs work almost the same way. Instead of an option to buy, RSUs are a contract to receive a share, for free, just like, “Hey, nice job, here’s a share of stock and a $10 Chili’s gift card. Don’t spend it all in one place. Well except for the Chili’s card, where I guess you have to.” If that sounds different from an option, it should be. A granted RSU for a $10.00 stock has an intrinsic AND fair value of $10.00 as opposed to zero for the option. So an RSU is more valuable from the outset, and it’s also more secure. The downside of an option in our example is you get nothing, absolutely nothing, if the stock doesn’t go above $10.00. The downside for an RSU in our example is whatever the share price ends up being (which could also go to zero, but usually doesn’t).

Options and RSUs are typically granted in return for a period of service at a company, the option’s vesting period, an important thing to know if you’re valuing your options in light of the fact that you usually hate your job and want to leave after eighteen months. Vesting periods are typically four years (or 2.67x job hating units), meaning you receive 25% of your grant each year. If you’ve been granted twenty options, then you’d be able to exercise five of them each year. If you’ve been granted twenty RSUs, then you’d receive five shares of stock each year. If you’ve been granted twenty Chili’s gift cards, hook a brother up with some queso.

All of this should be pretty straightforward, even remedial, for anyone working in technology. Let’s go to the accounting to understand how things might get funky.

Since options and RSUs both represents something a company gives to an employee in exchange for work, a company must recognize the impact of this non-cash compensation on its financial statements somehow. Unlike cash which should have roughly the same value in a year, an option or an RSU could have significantly different value depending on company performance, not to mention different values from each other. The company is granting something in the moment (which has periodic income statement consequences) that may affect the permanent capital structure (that is, the capitalization table). The result is that companies account for stock compensation in two places: as a non-cash operating expense in the period on the income statement and the full grant’s relative impact to the diluted share count.

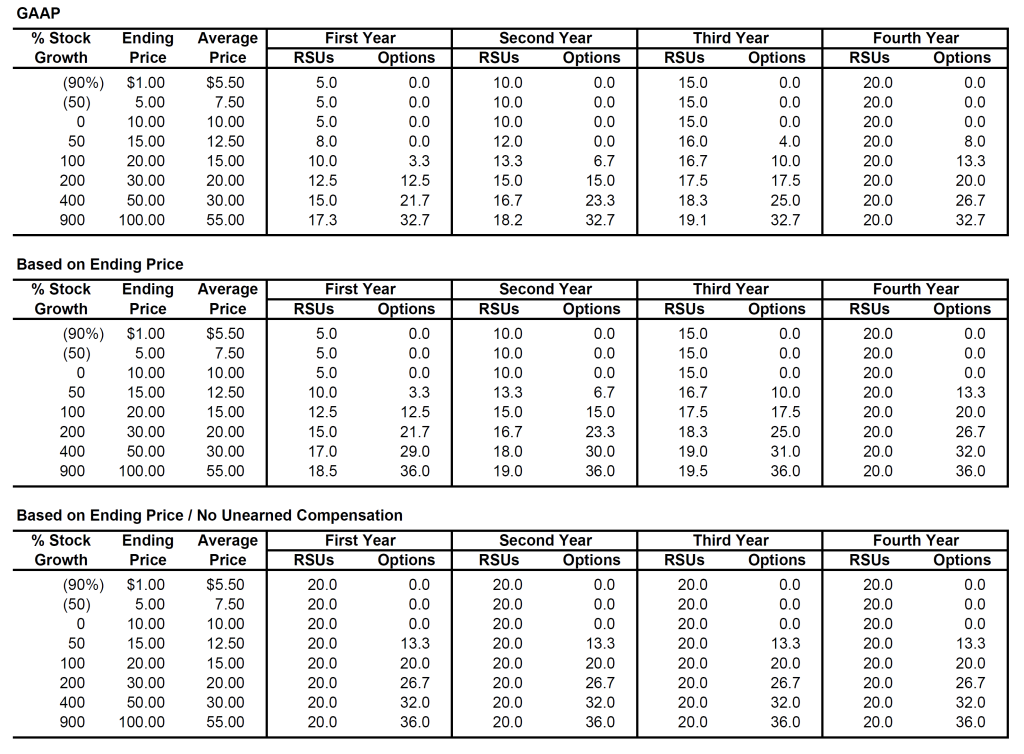

The periodic cash expense doesn’t change with the stock price value. Once you issue an RSU or an option, the stock compensation stays the same over the four years of vesting. You issue 20 RSUs at $10, that’s going to cost you $50 / year. You issue 40 options at a $10 strike price and $5 option value, that’s going to cost you $50 / year. The only reason non-cash stock compensation goes up is through the issuance of more equity instruments to more people, not through any stock price appreciation. And because a company can issue more options for the same price, the same dollar value of options will result in far more dilution as the stock price goes up, even if a single option will never be as dilutive as an RSU on its own. For the purposes of this example, the breakeven between options and RSUs is roughly at 100% price appreciation.

The takeaways from these past few paragraphs on accounting are these:

- Non-cash stock compensation on income statements doesn’t go up just because the stock has appreciated; it goes up because a company is issuing more equity at that higher price

- Options are more dilutive when the stock price goes way up.

- RSUs are more dilutive when the stock price stays the same or goes down.

We also have to figure out what the impact is of the full grant to the diluted share count, which tries to take into account the impact of dilutive securities on the capital structure. The typical practice is to net out how many shares the company can buy back versus what it doles out; we call this the treasury share method. For options, the company can buy back shares with the value from the cost of exercising, the theoretical value of unearned compensation not yet recognized (more on this later), and any tax benefits. For RSUs, there’s no cost of exercising. For simplicity, we will ignore tax benefits from stock options and focus on the other elements of the calculation: the exercise amount and unearned compensation.

For RSUs, shares are automatically added to the basic share count as they vest, because there’s no exercise provision. In the prior example, you’d get 5 new basic shares each year. Similarly, for the diluted share count, we only have to worry about unearned compensation since there is no exercise price. You take the $150 the employee is still owed, divide it by the current average share price, and assume you’re going to have dilution of the total unvested shares less this amount.

And why do we use unearned compensation? No one explains it well, not even PwC. The best explanation I found was a website half in another language that suggests “unearned stock compensation is a type of off-balance sheet asset in a sense: it can be used to offset future compensation expenses without bleeding cash.” Yikes. That’s just not how people work, even if I understand the math / matching principle.

For options, we go through the same process, except the company receives remuneration in the form of the exercise price. Vested options aren’t added to the basic share count unless they’re exercised, in which case, a cashless exercise usually takes into account the classic treasury share method for calculation. Otherwise, you take unvested, unexercised options and subtract out the amount you can buy back at the average stock price. Simple enough. Except once again, you also subtract the amount you can buy back from unearned compensation. Huh? Yes, it’s just like restricted stock. Too aggressive if an employee is leaving, and too conservative if an employee sticks around. The only reason why unearned compensation may work as a proxy for employee behavior for either RSUs or options is that if a stock has gone up considerably, it’s even more likely that an employee will wait out his or her vesting.

Let’s try to summarize this area:

- Fully diluted share counts don’t necessarily reflect equity issuance or what will happen. They reflect stock compensation that has already occurred and a best guess otherwise.

- Unearned stock compensation is not the best proxy for future share forfeiture; it’s based on stock price even though companies make assumptions about share forfeiture for periodic stock comp expense.

You may have noticed something else about these calculations. They all take into account the average share price during the period. Which means if you issue an option with a strike price for $10, and the stock price goes up to $50 by the end of the year, you’re calculating dilution using a buy-back price of $30.

Again, if that seems to be unreflective of reality, that’s because it is. So let’s add another thing to this discussion.

- The greater the stock price growth or decline in a period, the greater chance the share count will not reflect the operating reality of the capital structure.

In my research over the past few months, I’ve only found one guy talking about this. Professor David Doran at Penn State has been looking at these same issues and come to similar conclusions regarding the accounting. In his research published in the Journal of Applied Business Research in 2013, EPS would be more reflective of reality if companies used ending stock prices (a decision which FASB and IFRS came to in 2008 and then let sit probably because it was the hell that was 2008) and also if the diluted share count didn’t take into account the impact of unearned compensation as described above.

So what of this?

- We already ignore regular stock issuance as part of our discounted cash flow valuation. See Part II.

- We also ignore non-cash stock compensation as part of our multiple valuations assuming that the current share counts best reflect the capital structure. See, generally, Wall Street.

- Our accounting rules aren’t great at reflecting the capital structure, and the faster the stock price growth, the worse our accounting rules are.

- And while all of this is true regardless of whether a company issues stock or options, restricted stock looks a hell of a lot better on the way up to investors than it does on the way down.

In good times like we’re experiencing today, share prices go up while more shares get granted, vested, and issued. It may even result in a kind of multiple expansion as stocks prices get anchored to certain earnings levels despite rampant dilution. Of course, employees receiving these shares then spend their spoils on Bay Area real estate driving up home values and rents to the chagrin of everyone else who neither owns real estate nor receives free stock.

In bad times, the reverse happens. We don’t even know what a macro economic downturn will look like in a restricted stock era. Unlike unexercised options which will disappear as stock prices go down, restricted stock dilution is permanent for investors. Share counts stay the same while earnings go down and multiples contract. Plus those accounting rules that served companies so well on the way up will taketh on the way back down; using an average share price as the denominator for diluted share counts will result in a lot more dilution.

So then, what do you do? You might follow my new rule of “beware the growth stock that beats on EPS instead of revenue,” but otherwise, I will try to come back with some other… uh… options.

[1] Private company options work slightly differently due to valuations based on preferred stock and no consistent market valuation. I’ll talk about private company options at some point because I find myself advising lots of startup friends on their options.