ILLUSTRATION: Rejected from the Stanford Freedom Project #2: How I Wish Rocky IV Had Ended When I Was a Kid • watercolor on paper • 5×7″

Passing the overpriced gift shop at the Loews Santa Monica on my way to the valet, I attempted to make my escape from the pit of despair that was/is Digital Hollywood. The nerds-in-blazers-and-jeans look had not yet reached its crescendo, even in its birthplace. MySpace and Bebo and DRM were still real things on real conference panels. Outside Jason Calacanis jumped into a ridiculous looking corvette, and I laughed to myself “Ja ja ja, mach schnell mit der art things, huh? I must get back to Dancecentrum in Struttgart in time to see Kraftwerk.” It was 2006.

I had a quirky job working ostensibly in venture capital for The Carlyle Group. It said so right on my name tag which had just been noticed by an attendee looking for someone more important with whom to speak.

“Ah, The Carlyle Group? I would love to talk to you about something. You make investments in China, right?”

“Well, not me, but yes.”

“You’re big in real estate.”

“Again, not me, but…”

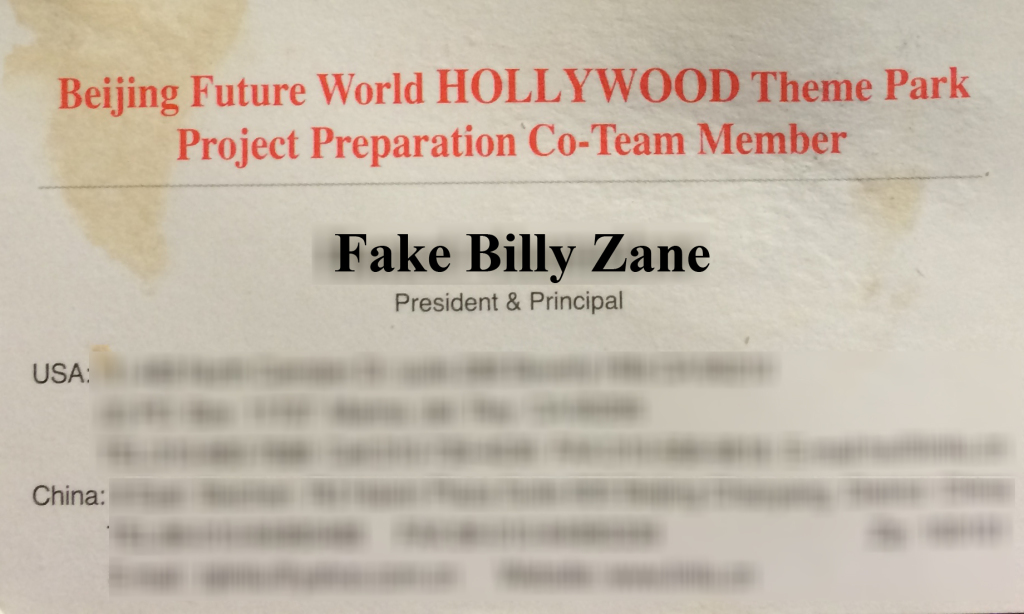

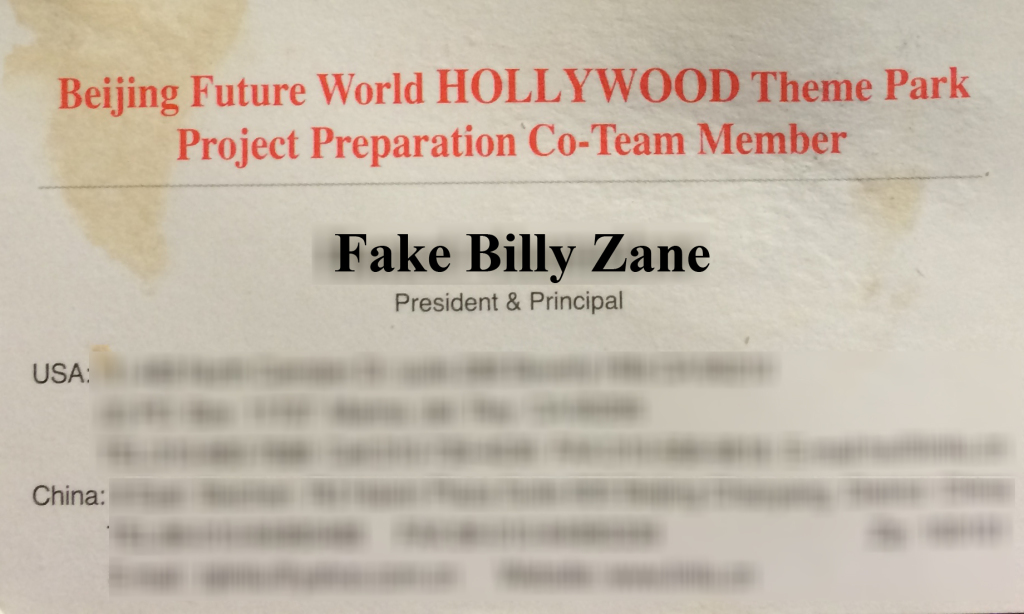

Given his resemblance, I’ll call him Fake Billy Zane to protect the innocent. Billy was a tall half-Persian, half-Japanese man who now lived in Beijing. Like me, he also thought the conference was going nowhere (you know, at least until it packed up for greener pastures at the Marina del Rey Ritz Carlton and talk turned to YouTube and Blu-Ray). But Fake Billy Zane was going somewhere. Fake Billy Zane needed capital. Big capital to fund big ideas. $100 million to build a theme park. The first theme park in Beijing.

His business card read: Beijing Future World HOLLYWOOD Theme Park.

Despite our conversation derailing somewhere between the stop for a commuter train that he claimed would land at the doorstep of Beijing Future World HOLLYWOOD Theme Park thanks to someone’s government bribes and the district I must visit where “girls in Beijing” would really love “getting to know” someone like me, I agreed to learn more.

“Okay. Lobby of the Fairmont at, um, 7… Uh, I have a hard stop at 8, ” I lied.

Fake Billy Zane chortled and slapped me on the arm. “And after I know you’ll come visit Beijing. I will show you a very good time.”

“Uh, there’s my car.”

I chose against jumping in Dukes of Hazzard/Jason Calacanis-style.

I’m not certain what I was thinking at the time. Okay, no, I know what I was thinking in a constant loop…

- “My boss had said his best investments came from the strangest places.”

- “Public place, public place, the Fairmont lobby is a totally safe public place.”

- “The Loews is much nicer than the Fairmont. I’ll have to book there next time.”

The next morning at 7am I was greeted in the lobby not just by Fake Billy Zane but also his boss: an older Chinese woman squeezed into a white, rhinestone, skin-tight, spandex mini-dress that stopped just short of the legal definition of indecent exposure. The clerk at the front desk tried not to stare and shuffled her papers over and over thinking surely that incidents like these were why she moved off the night shift. Let’s just call Billy’s boss Sally.

“Do you know Sally? She’s a famous former Chinese pop star, like China’s Britney Spears.”

“Wow. Very nice to meet you Sally,” I said, noting to myself that at somewhere between 40 and 70, Sally was really more like China’s Debbie Gibson or Donna Summer. Luckily there had been no paparazzi to capture what surely had been a flashy Spears-esque exit from their car. I gestured toward a giant ottoman-like table surrounded by chairs where I could listen to their presentation.

“Oh, first we take photos,” said Sally.

Of course, what investor meeting doesn’t start with photos? I’ll admit my naiveté on international manners in this context. The Japanese bring gifts and long presentations on their corporate structure since 1872. The Germans tease you for years that they’ll actually acquire something in-between mandated bank holidays every other week. Perhaps standard meeting protocol for Fake Billy Zane and Sally was taking photos. So I posed with Sally in the middle of the lobby of the Fairmont Santa Monica trying not to smirk at the desk clerk, as she facepalmed with one hand and gestured silently for the attention of her desk companion with the other.

“We’re very happy to meet with The Carlyle Group. We will add this to our photo album. You can see how excited others have been about Beijing Future World Hollywood.”

Sally opened a photo album where I was greeted by photos of Sally with politicians, dignitaries, celebrities, and business types. I can’t remember all of them, but I knew how they had answered when someone said, “Oh, first, we take photos.”

“Is that Jiang Zemin?” I asked.

“Yes. Yes. So surprised you know Jiang Zemin. Yes, indeed.”

Then I was directed to another picture with one of the President Bushes (I can’t remember which one) where Fake Billy Zane continued excitedly “And look! He is involved with The Carlyle Group too, no? Do you work with him?”

“Used to be. Used to be. No, no, I’ve never met him. I’ve only been with the firm for a year,” as I tried to manage his expectations and my now increasing concern over the odd, foreboding, brown paper envelope tied with string that I had just been handed. The type of envelope that holds a Grail Diary or bomb plans or, you know, anthrax.

Mind racing — I am not important, and I do not know important people. I was at Digital Hollywood. No one important goes to Digital Hollywood. It’s just a typographical error that the White House thinks my office is Frank Carlucci’s. I’m wearing jeans and a blazer, for goodness sake. — I unwound the string to open the envelope — Oh God, the news reports will say that the poison originated from an idiot who brought the envelope back to his office on a cross-country flight. I will be in critical condition and under investigation at a federal facility. I will whimper out a description to a sketch artist in Hungarian: “Keyser Soze! Úgy nézett ki, mint a hamis Billy Zane” — But inside there was no white powder to speak of, just a typical plastic-bound investor presentation.

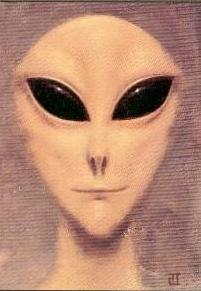

Except on the first page was one of those spoon-eyed aliens in a regal cloak holding court among the planets. And then more pictures of aliens followed on each subsequent page. You know, kind of like this.

“We wanted you to get a feel for what the theme park would be like. Space is very popular. Like Star Wars. Very popular.” I decided it would be rude to mention my childhood fear of these aliens (which hadn’t been helped by my mom taping up pictures of the aliens looking into my bedroom window as a joke when I was seven).

The presentation was mostly pictures of those scary-ass aliens interspersed with section headings such as “Financials” followed then by more aliens. Sometimes there were unlabeled grids with Xs and Os printed out on a dot matrix printer.

“That X is where we will build the theme park. Let me show you more.”

Billy reached for a tube and unrolled a giant swath of paper covering the ottoman and extending to the floor: a completely unintelligible topographic map of Beijing.

Imagine a map from an early 20th century war room where a general would chomp on cigar under a harsh uncovered single light bulb and signal his decision to attack by advancing troops across the map before then retiring to his tent to work on a spicy and sweet fried chicken recipe that would truly change the world. There were no roads, no city center, just contour lines and Chinese characters. It could have been Beijing just as soon as it could have been Kansas or Neptune. What with the aliens and all.

“Beijing Future World Hollywood Theme Park will be located here,” he pointed to a tiny shaded area. “You can see how close this is to Beijing. Just 25 minutes from the airport by train.”

“Uh huh.” Or close to Topeka. “And this train is going to be built?”

“Assuredly. We just need $100 million.”

“That’s a lot of money.”

“But we’ve run the numbers. Let me show you.”

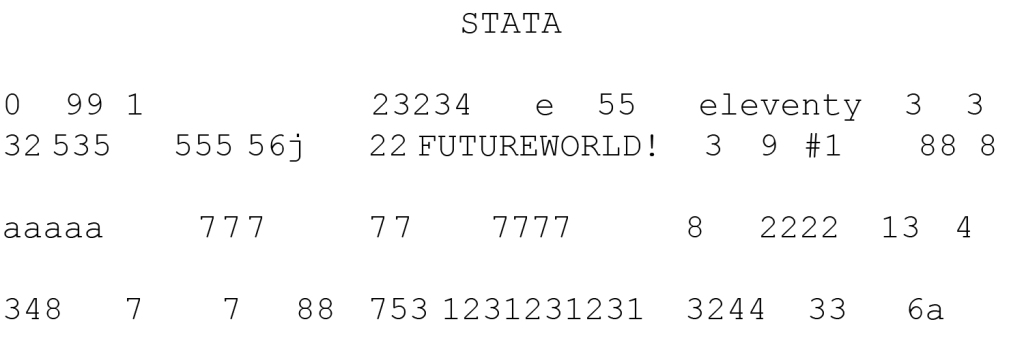

Billy flipped past more pictures of aliens to a page that looked like this:

They had run the numbers… all over the page. On what and for what purpose, I will never know. It could have been the paprika concentration in the Colonel’s Original Recipe. What is it with military leaders and fried chicken?

“So you can see how this will work. We’ve run the numbers, and you will make money.”

For some reason, it was the random page of Stata numbers, not the ottoman-swallowing map, or the rhinestone minidress, or the pictures of aliens that had once haunted my dreams that made me decide it was time to just play along with yet another deranged founder. “So $100 million?”

“Yes, and if you raise $100 million for us, I will give you $10 million,” said Billy.

“That’s not really how my job works.”

Fake Billy Zane and Sally chuckled. “We’re among friends. It’s only fair.”

“No, that’s not how my job works. We find investments, and I get paid for that.”

“You would be helping us out a lot. And in China, we help you too.”

“Erm.”

Fake Billy Zane winked as only a Fake Billy Zane can. “At the very least, you will visit Beijing soon. Sally, won’t the girls love him there?”

Sally’s coy smile grew to match the gleam in the rhinestones in her dress, and I returned the presentation to the brown envelope filled with unknown yet imaginary poisons, slapping it between my hands in earnest consideration and conclusion.

“Thank you, Billy. I’d love to visit. I’ll take this back to the China team and find out what they think. It’s very compelling. But I should get ready for my call now.”

A postscript. For what it’s worth, I did pass the deal along to the Asia team at Carlyle, and I’m surprised at the positivity and even-handedness of my email to my boss from then:

“Strange project fell into my lap. I was in the lobby of the conference, and a gentleman saw my Carlyle nametag and came over to talk to me. He was from Japan and working with a company in Beijing to develop a theme park and entertainment complex there on 8,000 acres of land they’ve been provided 25 minutes from the Beijing airport. He set up a meeting with me this morning, and he and his partner brought this massive amount of information on all the work they’ve been doing with the government, construction companies and real estate development firms. Very odd, but I wanted to pass it along to Asia Venture or Asia Real Estate just in case. According to their documents, they’re being backed by Guangdong Bank and are looking for foreign partners.”

And chances are, the Beijing Future World Hollywood Theme Park deal was real. The Atantic profiled the old Wonderland Amusement Park back in 2011 where they say re-development was attempted in 2008 and never got off the ground. The photos are haunting—a real-life Spirited Away—but the description and geography fit. It even sits near the Changping Railway just like Fake Billy Zane had promised me. Maybe I should have listened to my friend Fake Billy Zane. He was a cool dude. He was just trying to help me out.